Share this article

My travel series in Northern Nepal continues; I recently shared my inspiration from Tibet, Tibetan culture, architecture and traditions. After settling in Nepal in 1980 my curiosity strengthened; Nepal’s northern areas of high altitude, remoteness and strong Tibetan influence became more and more attractive.

Travel Inspiration

During my first trip to India in 1976, I bought a second-hand book ‘7 Years In Tibet,’ which I thoroughly enjoyed reading. Of course at the time, the movie had not been made yet and the story was unknown to most of the world. It carried me into another world; like a travel back in time with the idea I had of the Middle Age in Europe but with Eastern flavour full of possible discoveries. The best part, I realised with immense joy, was that these lands, its people and cultures, still authentically existed at that very same moment!

Tibet was extremely enticing for me because of its landscapes and architecture. The mountains, high altitudes and cold weather would win me over any day - over seaside and hot weather. The largely open and desert-like landscapes, with high mountain peaks in the horizon, always give me an impression and feeling of unconditional freedom and spaciousness; while at the sea I would feel quite the opposite - weighed down by the heat and trapped by the ocean…!

Of course as an architecture student, I was very aware of the beauty and intelligence behind Tibetan architecture. I was mesmerized, and still am to this day, to how well integrated it is to its landscapes. The images of the places I saw were very attractive; they depicted what seemed like a very modern style, with their cubic designs.

Today, their architecture is particularly adapted to the sustainable ideology. Take, for example the famous Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet; it is considerably modern in design despite it being built in 1645, at a time where access was difficult and availability of construction materials void. Yet, the Potala Palace and many similar structures were built remarkably high using only local natural resources.

Tibet and its surrounding areas attracts me in many other ways. At that time, I was drawn to the simplicity of living; the very lack of resources presented challenges and opportunities to explore freedom in creativity to make everything – from building, making textiles and crafts to food - from scratch.

About Tibet & Northern Nepal in the 1980s

The book ‘7 Years In Tibet’ aroused a deep curiosity. I wanted to know more about this culture and dreamt of having the chance to wander in Tibet freely. Unfortunately, it was really not possible at that time in 1980. Tibet and its neighbouring kingdoms were closed to foreigners and was quite dangerous to enter without a permit. Tibet officially opened its borders to foreigners only in 1986.

As I researched more into the area I heard about Mustang, a far North District in Northern Nepal, which at the time was virtually independent due to its remoteness, difficult access (only accessible on foot) and still under the rule of its own King. Mustang held ‘untouched’ Tibetan culture, yet inside the boundaries of Nepal, and even though it was also a restricted area, I figured I could still find a way to go, especially if I could speak the language!

Tangye | Upper Mustang

At that time, these distant Northern districts of Nepal were still very remote with no road access and where locals still spoke their own local tongue. Most locals could not even speak their national language - Nepali - and formal education had not yet reached such remote parts of Nepal.

From what I understand, these remote Northern areas were restricted to foreigners for several reasons. The main reason for it was the scarcity of food; there was only just enough for the local people. In the case of Humla, in far west Nepal, not even enough for the locals so they could not allow trekkers to rely on the local food.

Control over the borders also seemed impossible; with the proximity to Tibet and lack of check posts, assistance to any foreigners who need it would be difficult to manage, or even be known. Telecommunications also did not exist - therefore it seemed easier to restrict the areas altogether.

The restricted areas finally opened to foreign visitors in the 90s - despite the Nepal-Tibet border already open in the 80s - but are still strictly regulated with costly entry permits for foreigners. Nonetheless this helps to preserve balance in such fragile eco systems.

Preparation for the trip

My desire to visit Mustang heightened and I just had to realise my dream. With this purpose in mind, I began to study Tibetan Language at the French Oriental Language Institute in Paris between 1977 and 1979, in parallel with my architecture studies. I vividly remember remarks from a peer, thinking I was crazy to do both and I would certainly drop the idea of learning Tibetan as he thought I could not manage both. Of course, with my type of determined character, his remarks put me up to a challenge – and as I anticipated, I succeeded.

The combination of architecture studies and Tibetan language presented an interesting resource and knowledge base and led me to meet with various anthropologists and friends in Kathmandu. One person in particular - who becomes the centre of all the subsequent events that follow - was Corneille Jest. At that time he was heading the Himalaya section of the CNRS (National Centre of Research in France).

In 1980, during a trip back to France, I met him and he advised me to go to Menri Sarpa, a Bön monastery not far from Simla in North India. Eager to learn, experience and explore the closest to Tibetan culture, I embarked on a one-year trip to India where I could practice spoken Tibetan in various monasteries and Tibetan settlements - in particular Menri Sarpa Monastery where I spent one month and a half gathering data for an architectural study.

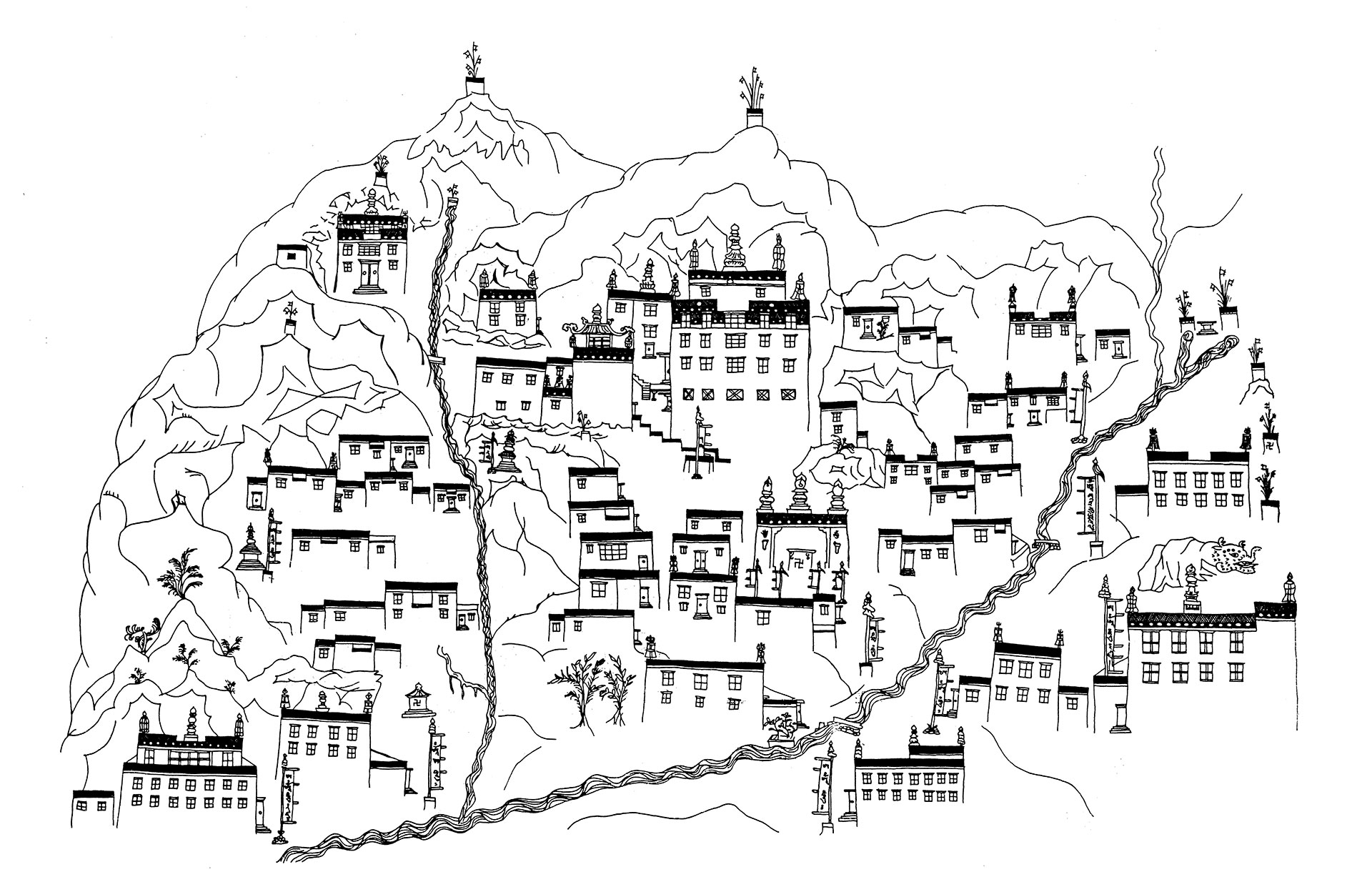

Menri Sarpa monastery took its name from the old monastery in Tibet, here represented in a typical tibetan style drawing

It was here that I was introduced to Bön religion and its culture and also had the opportunity to meet two high Bön Lamas: Lungtok Tenpa’i Nyima Rinpoche and Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche.

Bön (Yungdrung Bön), the native religion of Tibet, is one of the world's most ancient spiritual traditions. It has a unique and very rich heritage. It is told to date back 18,000 years ago. [read more about Bön]

A Bön mantra (a sacred utterance) engraved on a stone “OM MATRI MU YE SALE DU”

At the start of 1981, I was ready to take another leap into my journey. I could speak Tibetan fluently enough and I found myself setting up my base in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Whilst living in Kathmandu, I was determined to make my dream a reality. However, I realised that establishing safe – and incognito – entry and exit to Mustang was extremely challenging. Due to its geography and the trails that were available to trek, I would have had to exit the area via the same route that I entered – this posed some risks.

Anyhow, I did not give up on the idea.

Thanks to my stay in the Bön monastery in India I learned about Dolpo, another restricted area of Tibetan culture in Northern Nepal (West of Mustang) with several Bön monasteries. It seemed to offer an even more interesting journey and mapped out somewhat ‘easier’ and less risky paths to enter and exit (unnoticed) thanks to its geography.

Although the final destination was shifted from Mustang to Dolpo, I nonetheless knew this trip would be nothing short of challenges!

Planning the Dolpo Route

I continued to work on my journey to Dolpo, far and remote, and untouched by foreign influence - genuine and authentic, just as I like anything to be! It would somehow seem like I was going to Tibet.

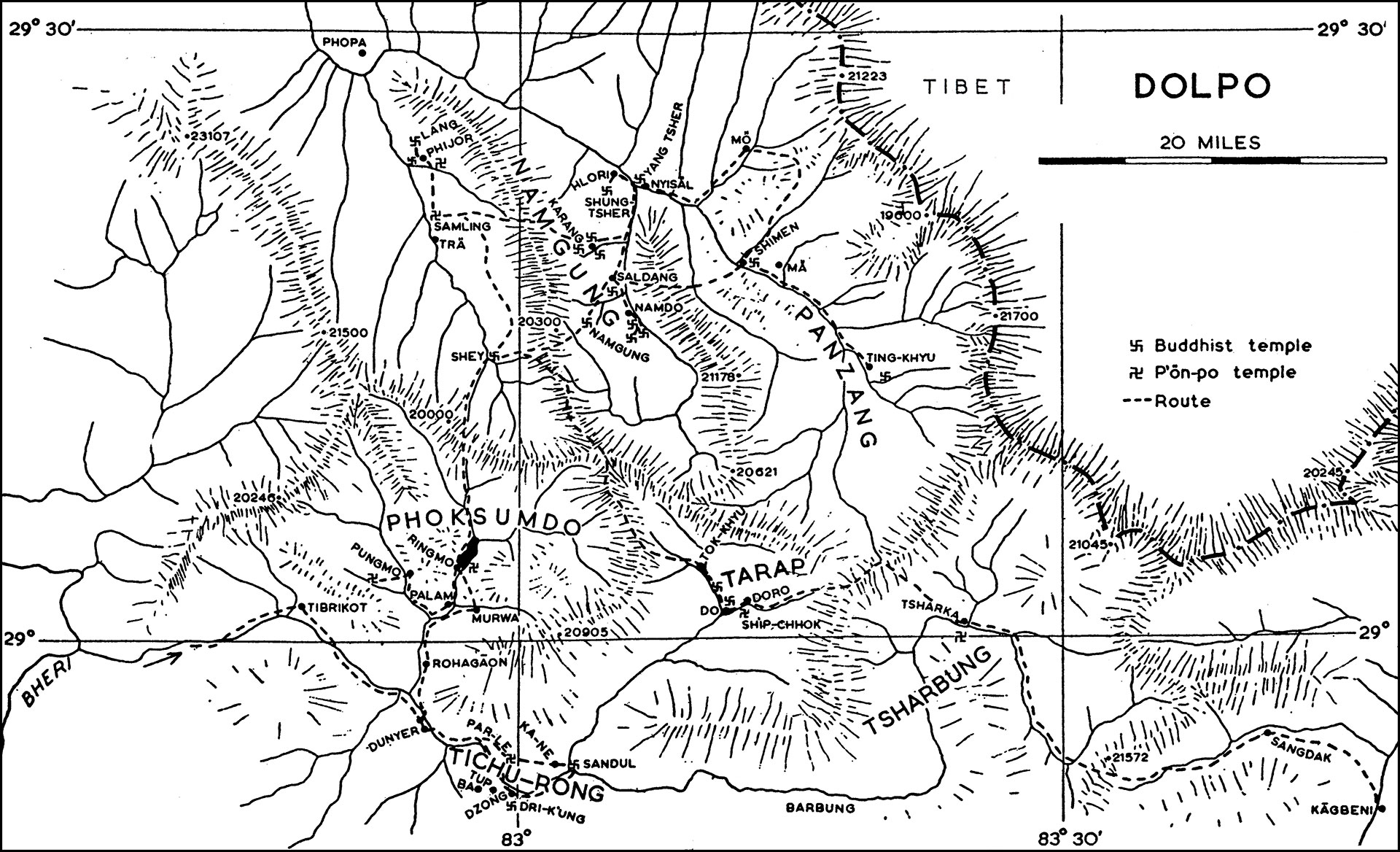

Based on information I obtained through a friend and from the book I managed to get my hands on by David L. Snellgrove ‘Himalayan Pilgrimage,’ my plan started to take shape. I copied the map from the book, which indicated routes that also highlighted which monasteries are Bönpo and which ones are “Chöspa” (Buddhists).

Incidentally the author of this book was the one who invited two of the highest Bön Lamas to England – who I had met in India - in the 60’s and they returned to India to establish a Bön monastery, the one in which I did my study.

The Map from ‘Himalayan Pilgrimage’ was extremely resourceful at a time when such detailed maps were not available – of course understandable considering there was no tourism there. What was even better and more useful was that the author used actual village names spoken by the local population and not the ‘new’ transformed Nepalese names (that most locals did not understand!)

What I knew undoubtedly was that this trip to Dolpo had to be extremely well organised – I could not afford to stay in the same place for more than one day, otherwise I would risk getting caught.

Without much money or belongings, I borrowed some necessities to take with me on this adventure to Dolpo: a sleeping bag, a down jacket and a camera! At this time, I realised, what seemed like just an idea, a kind of dream, is now turning into a reality.

Feelings of excitement elevated. The fact that Dolpo was forbidden made it a daring experience but I was more enthusiastic to go because it was untouched – a little like traveling back in time in the middle ages as it has been in Asia, in the Tibetan plateau for hundreds of years.

The plan was to fly to Jumla a small town in Far East Nepal and walk east towards Dolpo. I chose this route so that for some part of the travel I could say I was going to Pokhara (another popular touristic town in Nepal) to avoid suspicion. Once I reached Jumla I was to search for someone who would agree to accompany me on this journey – someone local, who knew the trails. I knew this would not be easy but I trusted to follow my intuition on who to trust. Still, that was not easy!

The idea of traveling alone to Jumla was not something my friends took lightly. Most were quite worried and one of my Tibetan friends introduced me to Tsering. Tsering was to accompany me and protect me during the journey. He was belonging to the famous Tibetan warrior tribe known for their strength and courage, also known as a ‘Khampa’ from Kham in Eastern Tibet. Tsering was a tall and strong man and at that time certainly gave me the feeling of protection.

Tsering was well aware of the situation and the journey that would involve entering ‘forbidden’ Dolpo. Nonetheless he agreed to join me and we began the journey with a flight from Kathmandu to Jumla. I knew this journey would take time and I may be away for one, or two, or even three months.

Starting the journey

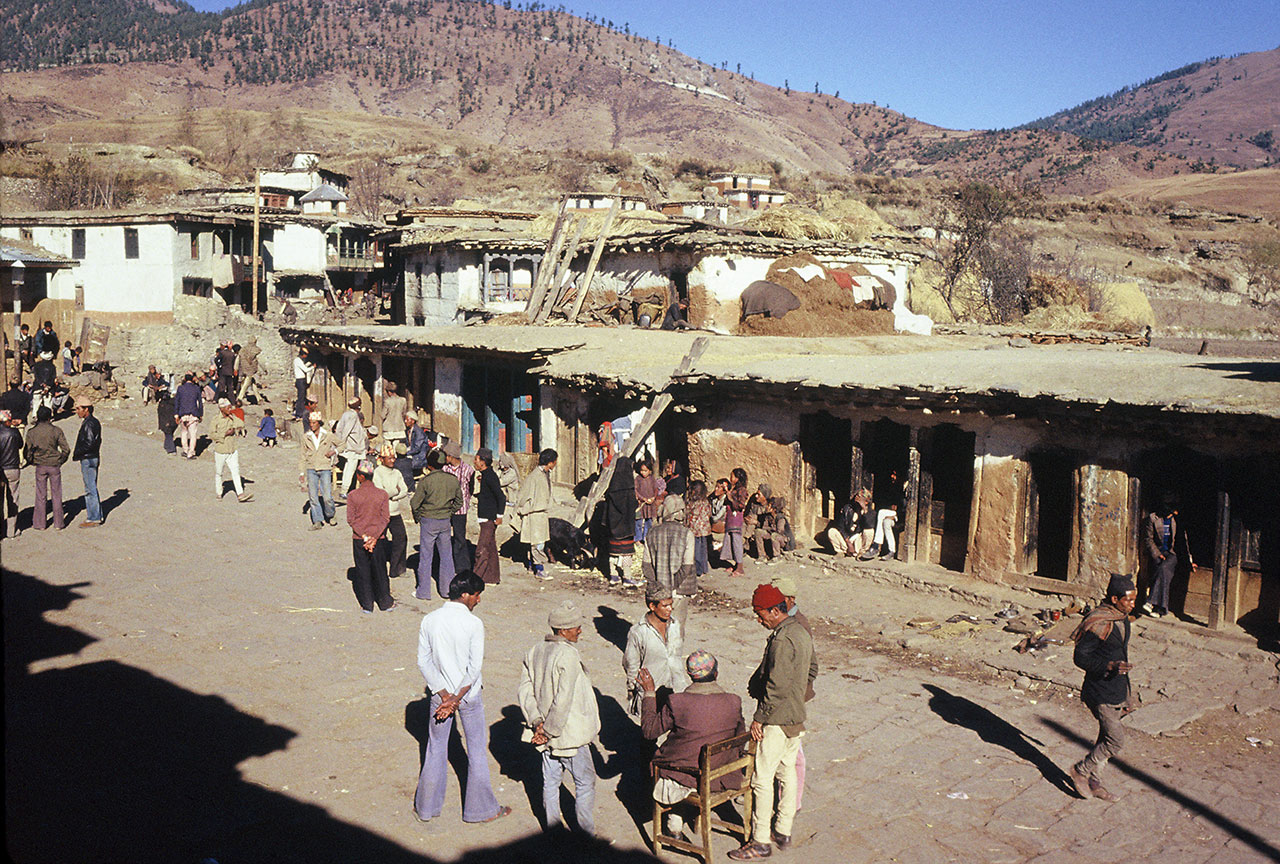

A village chief official sits in the centre of a square in Jumla being greeted by locals as they pass by.

Arriving in Jumla was already such a change of scenery and culture – already a contrast from what I experienced in Kathmandu valley. There was no road access, only small planes flying there carrying 16-18 passengers. Here there were few shops with very little variety of goods available; only the most basic items like grains, lentils, oil, limited spices, matches and potatoes (and often not even the most basic items are available). At that time, rice was an expensive commodity (maybe double or triple the price in Kathmandu) and only ‘well off’ people would indulge.

I had already reached quite a remote area even though any foreigner could travel there. But apparently very few did at that time.

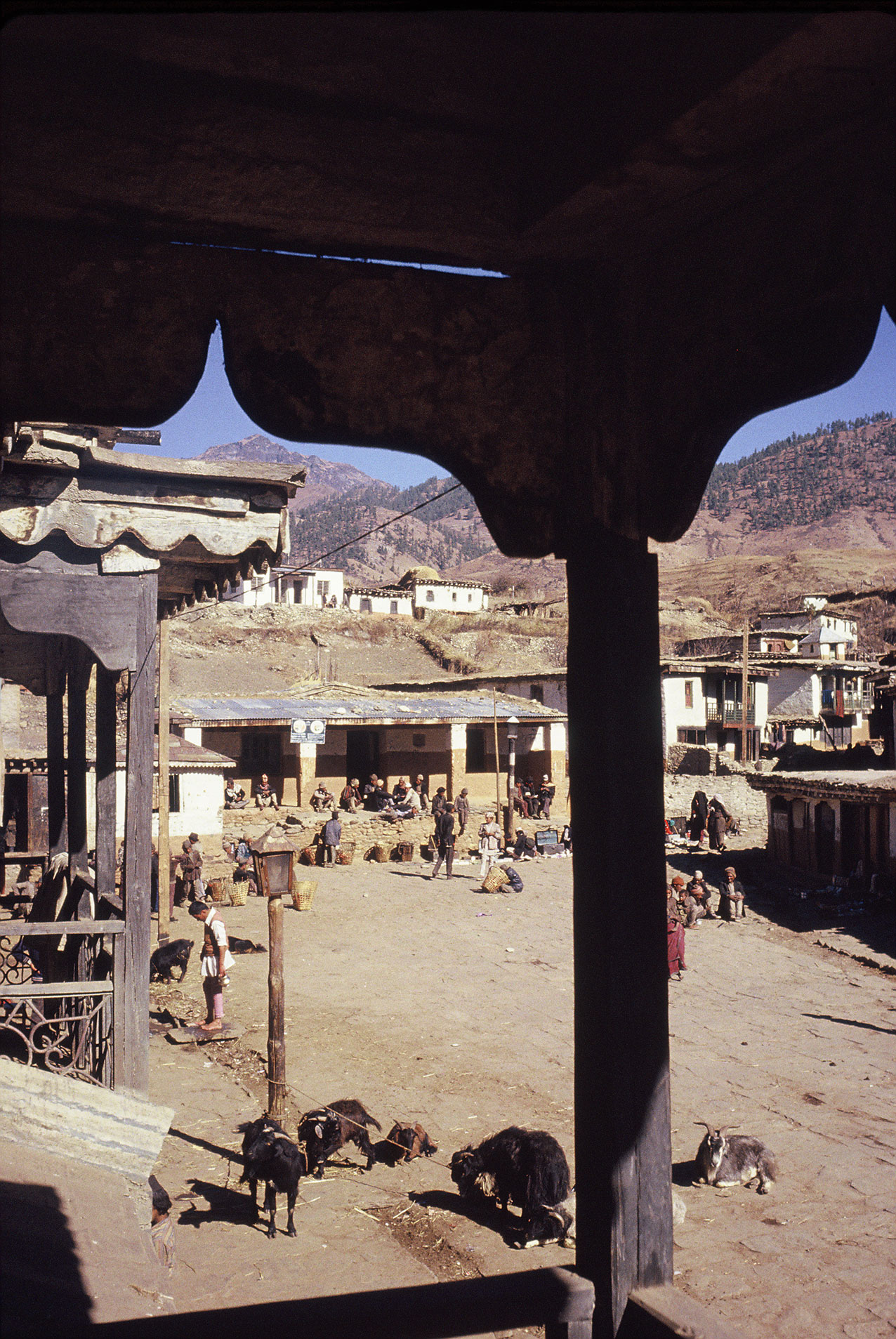

Here in Jumla, some of the features of the local architecture were already similar to the Tibetan architecture I would come to see further north. Houses - somehow built on top of each other unable to recognise where one house starts and the other ends - presented flat roofs similar to those in Tibet. The buildings were very basic, made with local raw materials, most of it done by hand which gives a kind of agreeable and attractive irregularity which I find so lively!

Another view of Jumla's main street and at that time basically the only street of a tiny village with its own airport.

With hopes not to spend too much time in Jumla, we settled into a small ‘homestay’ taking care that no one would guess our travel intentions. I was the only foreigner there at that time which aroused curiosity amongst the locals and did not help to keep our plans discreet. As soon as I would step outside onto the main street, a group of locals would form around me, simply to gaze at me as though I was a strange animal. I had already often experienced similar occurrences in India so I was not too surprised but this did not help me stay unnoticed.

On the very first day in Jumla, Tsering and I met Nyima, a young man from a nearby district, and right away I knew I could trust him. He had travelled through all the nearby areas and already been several times to Dolpo. As I began to slowly unveil my travel plan and intentions, Nyima grew confidence and was happy to be my guide. Being a Bhotia (a person of Tibetan culture and descent) he was pleased to know I could speak Tibetan.

Right away, we began to get ourselves organised; collecting food, matches, candles and whatever we may need during the travel. We knew it will be difficult – or practically impossible – to buy food and other ‘basics’ on the way. I also bought some clothes and shoes for Nyima – he barely had any equipment or appropriate clothing. With so many uncertainties, we took what we could carry.

As Nyima and I were finalising our incognito route, Tsering – my supposedly protector and Tibetan warrior – started to feel frightened. Out of all people! I was so annoyed at this; instead of being an asset he was quickly becoming a burden. Looking back, it was somehow laughable - this tall and strong looking man was scared while Nyima, thin and much more delicate looking was not. The appearances definitely do not make the man!

Nonetheless, we were finally able to start our journey on foot, having organised to join a caravan of Yak returning back to Dolpo. We would meet them along the route after a two to three days walk.

By this time, we had spent around a week in Jumla - it was really time to go.

Samling Monastery | The kind of arid landscape and lost settlement I was looking forward to.

Don't miss the next part of this travelogue and adventures to Dolpo and Northern Nepal.

Subscribe to be the first to know.

About Marina Vaptzarova

Designing and creating conceptions has been part of her professional life for over 25 years. During this period, Marina revisited the traditional raw materials, craftsmanship and skills of Nepal and transposed these into contemporary design handicrafts and accessories. Her designs are fully experienced by the customer and play a prominent role in addressing the needs of the hospitality sector.

Marina Shrestha is a specialist consultant designer for interior handmade accessories in the hospitality sector, particularly in the luxury boutique segment. She also provides consultation on product development for handmade crafts.

Share this article