Share this article

This is part 4 of a series about my travels to Dolpo. Read Part 1: Planning the Journey, Part 2: The Road to Dolpo & Part 3: ?

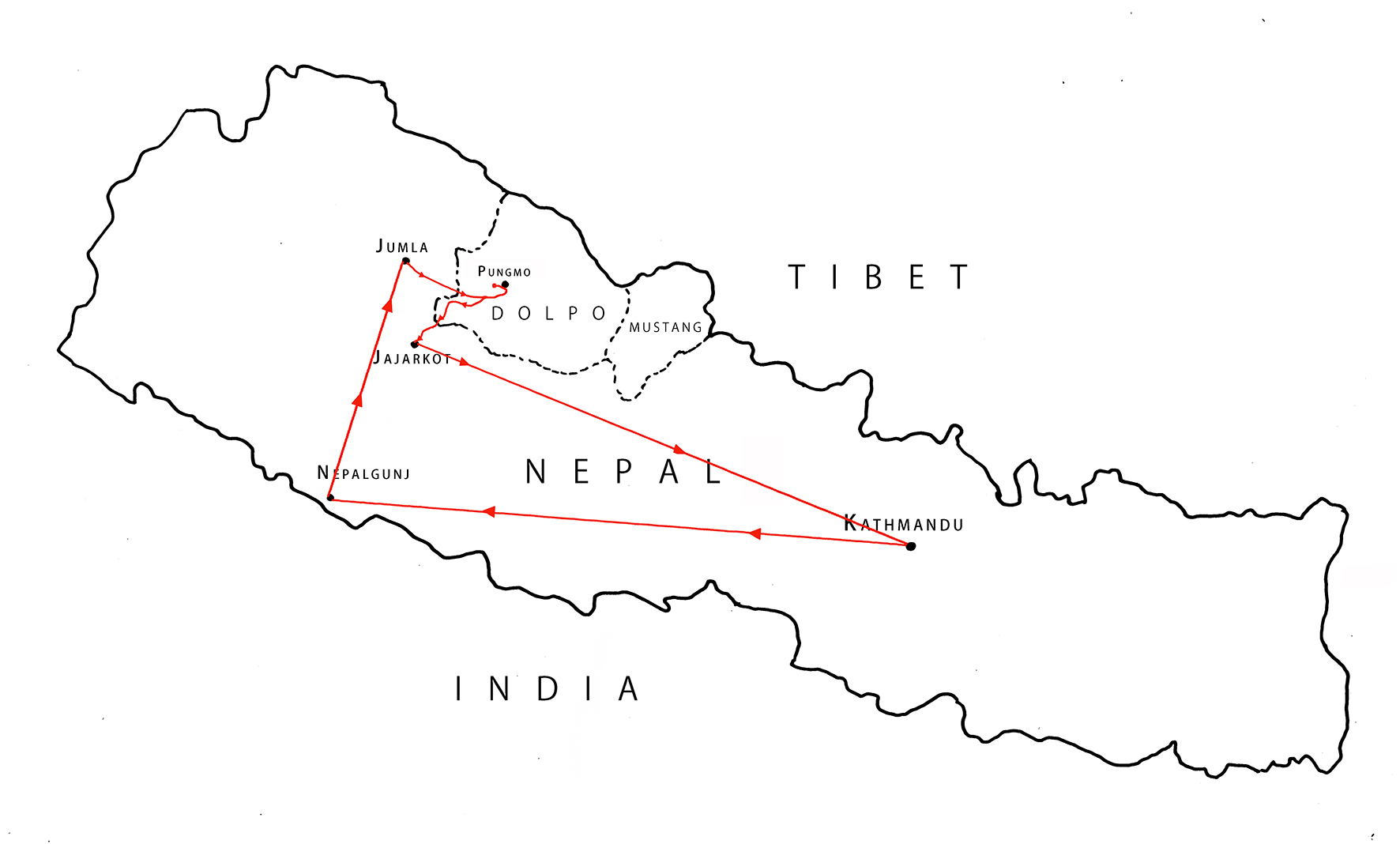

Dolpo – Jajarkot – Kathmandu

Our days in Dolpo had to come to an end. I was saddened to leave Thegchen Rabgye Ling monastery. Despite being there for only a few days, I felt so warm and so much at home, as though I had spent a long time in that place. I somehow felt very familiar with their way of life.

Nyima and I began our return back via Tibrikot, then followed another mountain path to the south, along the Bheri River. Our original plan was to return via Pokhara, but this was no longer affordable. Instead we chose to go to Jajarkot, where there was a small airport, or rather just a small runway, and I was hoping to hop onto a plane back, directly to Kathmandu.

Again, Nyima and I find ourselves walking alone in the mountains; a journey that would continue for many days. After a few days two other Nepali men joined us. Once we reached the hilly region further south we experienced the most intense of situations; a kind of discrimination I had not experienced before, definitely not in Dolpo.

In these areas the Hindu caste system was very prevalent. We soon became very well aware of which houses we could not enter – especially not in their kitchen. Sometimes we even had to sleep under a shed outside and we were mostly fed outside too. At the time, a Hindu kitchen would be located on the top floor along with the prayer room; these were considered the most sacred areas in a house that should be preserved from outside spoiling, from anything impure. This was the case for most of the houses that belonged to the Brahmins (priest caste) and Chhettris (warrior caste). It was believed that by entering their homes we would bring in with us impurities. It was, and to a certain extend still is, believed that lower castes were deemed impure, and to me this was heightened because I am not part of any caste.

Nevertheless, we managed the situation and it somehow became the centre of our jokes, which made good laughs between the four of us going through this experience. In these cases, Nyima would translate to me from Nepalese to Tibetan.

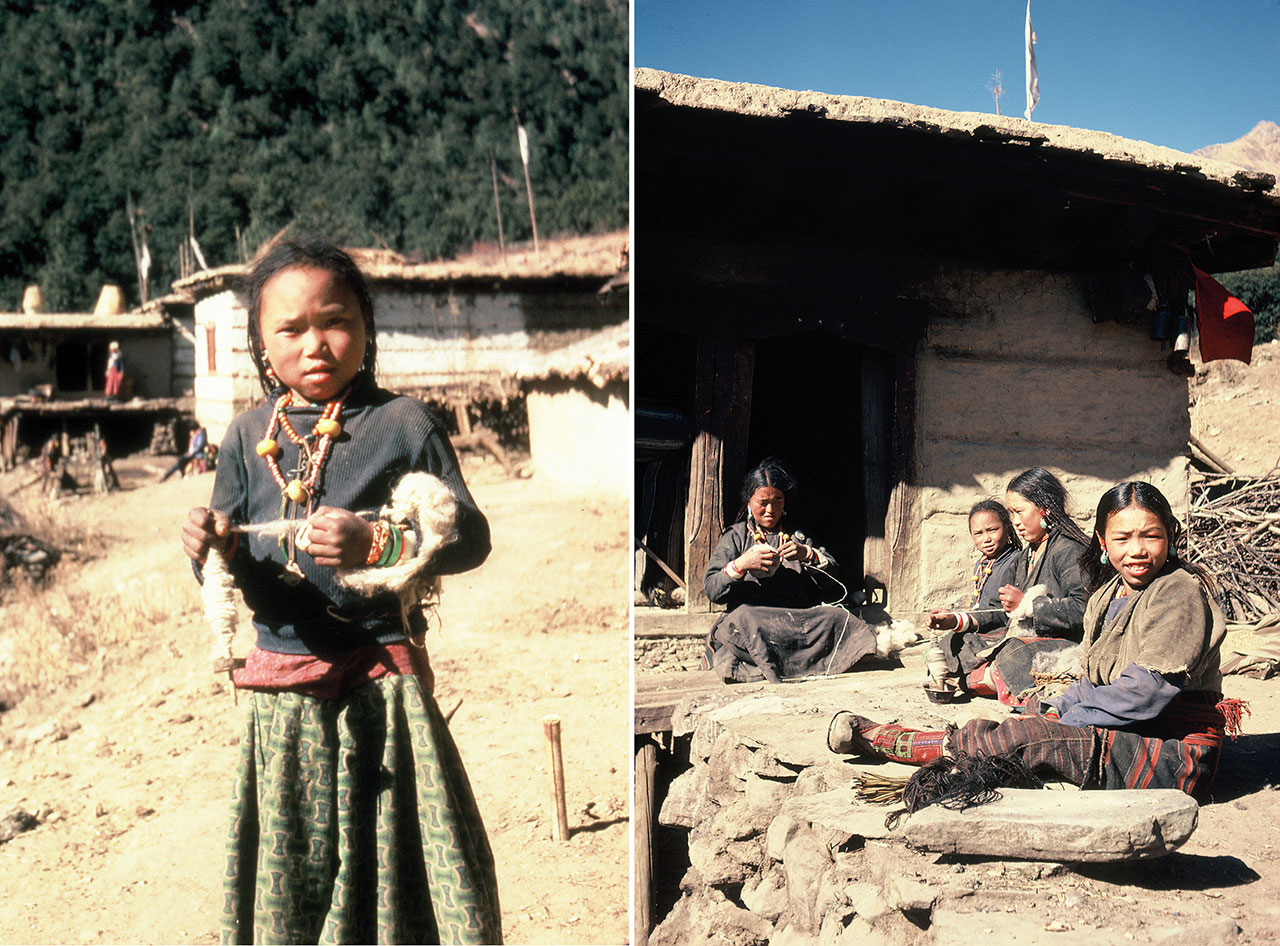

I interestingly discovered that in the Western Nepal hills, amongst many communities, it is the men who do the knitting. I remember one of the Nepalese travelling with us was also knitting. He later met someone else on the road, also carrying his knitting gear, and they astoundingly shared and compared designs and techniques. This was quite a surprise to me! On reflection, I found that we are so much taken by our habits and ‘social norms’ from where were brought up that such a thing seemed surprising to me.

A mix of cultures | A local woman dressed in typical Nepali clothing wrapped with a traditional Dolpo skirt in lower Dolpo as we began our journey back.

The journey continued, and as predicted, never void of any potentially dangerous situations. As we continued along the Bheri River, we hiked and slept in areas known to have bandits. We were advised to stick to a group of at least 10 people when sleeping outdoors, otherwise we should continue walking until we reach a village. One tiring day, we had to walk over 10 hours to reach a settlement. Despite the practice I gained of walking for weeks, I was exhausted. I remember that once I sat down, I felt I could not move anymore.

The days were long, walking vast distances from village to village in these still very remote areas. Although this area was not forbidden (I managed to exit successfully!) there were no foreigners around, the consumption world was far away; no shops, just a tea shop from time to time. I felt I was in another dimension, another era, a world very different from mine. As I look back, I remember this was also rather relaxing.

Finally, Jajarkot was nearing. I was concerned that they would not take me on a flight as I did not have enough money to pay for the fare. Nyima and I discussed how to go about this and finally decided that I should appear sick to people who we encountered on our way so that the story would hold. So I pretended to be sick and the urgency had to be felt!

Upon reaching the small airport in Jajarkot, I proceeded to the tiny Royal Nepal Airlines office, pleading to let me on the flight and pretending to be ill beyond belief! I even went to the extend of planning a collapse without getting hurt! But that drama was not necessary. I guess they could not bear the responsibility of a sick foreigner. In exchange for my small tent as a deposit, and after mentioning the name of a pilot I knew that worked with the airline, they sent me off on the next flight to Kathmandu.

It worked! We departed from the forbidden land of Dolpo, smoothly. Reached Jajarkot, many days later, at 10am, safely. I sat on a small 18-seater aircraft (twin otter) at 12 o’clock, shiftily, and by 2pm I was back in the bustle of Kathmandu, devouring a rewarding meal at my friend’s restaurant!

Not to leave any loose ends, I contacted the pilot and he sent the payment for my plane ticket to Jajarkot. Two days later, I went to fetch Nyima at the airport in Kathmandu and there he was, holding my tent I left as a deposit! He wanted to come to Kathmandu to buy some necessities that are not available in the mountain regions. He was able to do this with the payment I gave him for this excellent service. He, really, had been a great guide and pleasant company during my one and a half month adventure to Dolpo and back. In the end everything worked out perfectly. Nyima had really been the best guide I could have ever wished for.

Back in Kathmandu | Travel Reflections

After one and a half months wandering in the mountains, I was back in Kathmandu. The stark contrast was definitely felt; in a blink of an eye I was amidst a bustling town with shops, and so much variety of food and amenities.

During this trip to Dolpo I experienced the local way of life amongst so many ethnic groups of Nepal. I shared their food and slept in the same shelters and homes. In Dolpo, hospitality was second-to-none, despite the little they had to offer. Notwithstanding the simplistic and basic way of life, the culture, traditions and sense of spirituality was incomparable. We have a lot to learn from such ancient cultures. Even though I could not travel extensively in Dolpo, arriving in time for the auspicious three-day purification ceremony was a true gift.

It is unconceivable to think how people live in those remote areas, especially at that time, where all travel and communication had to be done on foot and with very limited access to anything else other than what was available on site. I am not sure I am able to describe the utter simplicity and ruggedness of this lifestyle.

The rural communities were spinning, weaving and stitching their own clothes and growing their own food. They were mostly self-sufficient with just some barter business for salt and a few commodities. They seem predominantly contented and hold strong community bonds; always helping each other when required. In fact, they were living a very sustainable way of life – a concept we are today struggling to attain or go back to!

I also discovered very beautiful and unique crafts, most notably Dolpo’s striking weaving that use such simple techniques but create such stunning textiles!

Interesting to note that in Dolpo women are spinning and weaving but the men are the ones stitching; a balanced repartition of the tasks.

Later on, when Dolpo opened to foreigners (a few restricted areas were open to tourism in 1989), I returned with my husband and my children on a few occasions. The first time, in 1995, we flew to Jumla and hiked along the same route I did in 1981.

Thereafter, in 2009, my husband and I finally made it to Upper Dolpo and to Samling Gompa, the famous Bönpo monastery I wanted to reach so desperately! With no doubt, the journey was arduous, full of unexpected happenings and difficulties but we made it. This time it was more like a pilgrimage since in 2005, we had started following the teachings of the eminent Bön Master, Yongdzin Rinpoche, whom I had met in 1980 in his monastery in India. Somehow all was falling into place.

The links continue as I became close to Corneille Jest, who somehow was at the centre of all these adventures - in my travel journey as well as my spiritual journey. Corneille Jest also spent several long stays in Tarap, Dolpo, earlier in the 60’s, so we had a lot to exchange about. Thanks to him, I went to the Bön monastery in India, which then took me on this voyage to Dolpo, and later to follow the invaluable teachings of H.E Yongdzin Lopon Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche.

I can say that this journey has had a strong impact on my creations. Unique Dolpo weavings, traditionally worn as belts, were used to decorate photo album book covers I designed. I succeeded to source the belts through a WWF representative in the area who organised the manufacturing. The typical Dolpo belts were all different – unique as it was intended - all hand-woven with hand-spun wool, completely made by hand from scratch. Dolpo’s unique culture and craft now had a new audience and appreciation in France.

To this day, I continue to be inspired by this journey and by all the crafts and Tibetan-rooted traditions I observed. I feel I still have so much more in store to create from all this inspiration. Despite my eagerness to design and see things to their fruition, things take time to produce. As a designer for handmade lifestyle products I always advise that one should not be too much in a hurry to get results.

There is more value in an object that is carefully made, one at a time, with appreciation for the raw materials, the skilled craft and the final outcome. This handmade connection is irreplaceable.

Dolpo Guestbook

About Marina Vaptzarova

Designing and creating conceptions has been part of her professional life for over 25 years. During this period, Marina revisited the traditional raw materials, craftsmanship and skills of Nepal and transposed these into contemporary design handicrafts and accessories. Her designs are fully experienced by the customer and play a prominent role in addressing the needs of the hospitality sector.

Marina Shrestha is a specialist consultant designer for interior handmade accessories in the hospitality sector, particularly in the luxury boutique segment. She also provides consultation on product development for handmade crafts.

Share this article